As I walked into the large room, people moving in front of me, I looked up and saw ‘The Duke’. Our eyes met, a shiver ran down my spine. OMG! IT’S A GOYA!!!

If you are wondering about my delirium over this work, apart from the fact that it’s just a bloody marvellous painting, it’s because paintings by Goya rarely make it to our shores. I did a quick check and the only Goyas permanently in Oz are of Goya’s Los Caprichos series of etchings.

I was also surprised as nowhere in the pre-publicity for this exhibition did I see a mention of a Goya, nor Vermeer or Velasquez, all of whose works were in the show.

Arthur Wellesley, the 1st Duke of Wellington, (1769-1852) was arguably the leading military (and political) figure of the 19th century in the United Kingdom. His most prominent victory was the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo alongside the Prussian army under Generalfeldmarchal Blücher.

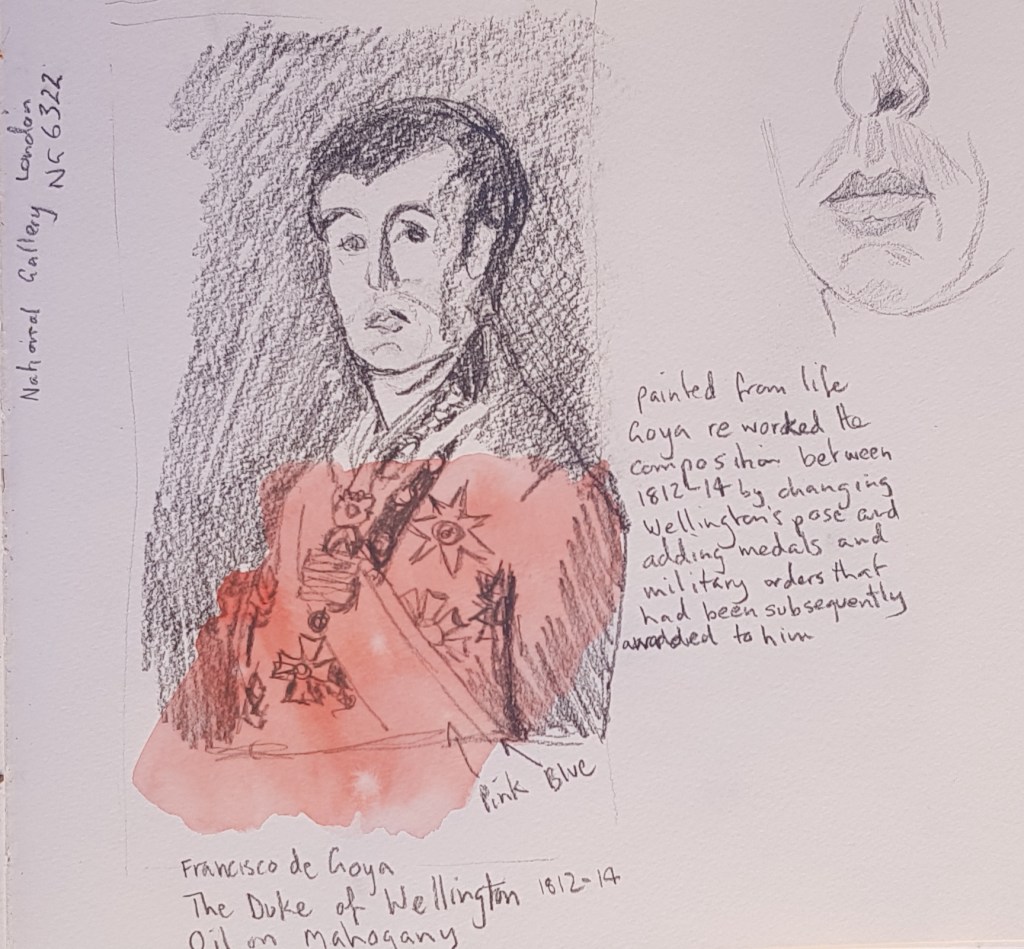

As this was my second visit to the exhibition (see my previous post here) I decided to prepare my page with a splash of red paint. This reflects the colour of the Duke’s uniform, but I wasn’t trying to be literal about painting it.

I also chose to do a closer study of the lower part of the face. By this time I had realised that trying to replicate the fine modelling of the oil paint was more than my pencil could manage.

The actress of the title is Mrs Siddons (Sarah Siddons, nee Kemble, 1755-1831). A famous tradegienne she was renowned for her portrayal of Lady Macbeth and Isabella from Isabella, or The Fatal Marriage by Thomas Sotherne. As an interesting aside, Siddons also played the role of Hamlet on numerous occasions over a 30 year period.

The portrait of Siddons in the exhibition is by Sir Thomas Gainsborough (she was also painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds and Sir Thomas Lawrence whose work is also included in this exhibition). Her head is shown in profile with her powdered wig and her dramatically large hat framing her face.

William Hazlitt said of Sarah Siddons “Tragedy personified … to have seen Mrs Siddons was an event in everybody’s life.”

The final grace note was to find out, via Wikipedia, that the Duke and Mrs Siddons were acquainted, as the Duke attended some of Mrs Siddons receptions.