This past weekend I visited the National Museum of Australia to see the exhibition Encounters: Revealing Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Objects from the British Museum. The exhibition also provides links to contemporary Aboriginal people and communities via a series of videos that give the visitor an insight into their view of these items. But is an exhibition that is based on a paradox. That is that many of the objects on display were taken (read stolen), without permission from individuals or communities. Yet these objects would almost certainly have not survived this long, due to the perishable nature of their construction, had they not been taken. In several of the videos I watched, people commented on how they had gained both practical knowledge and cultural strength from interacting with these objects.

Two spears, taken by Captain James Cook and his men on their first encounter with Dharawal/Eora people in Botany Bay in 1770, form the literal centre of the display. The rest of the exhibition turns around this focal point in Australian history. As a ‘maker’ I love looking at the details of these spears, the long flexible prongs still bound tightly to the hafts of the spears. At the same time I was horrified to know that these examples, out of some 40 spears collected at the same time, were taken after the local people, who tried to stop Cook’s attempts to come ashore, had been shot at and driven away by the landing party. Sir Joseph Banks wrote in his diary:

“[We] threw into the house to them some beads, ribbands, cloths & c. as presents and went away. We however thought it no improper measure to take away with us all the lances which we could find around the houses.”

Gweagal fish spears collected by James Cook at Botany Bay (foreground), with contemporary fish spears (background)

Before I tie myself into a total knot about my feelings about how many objects in this exhibition were ‘collected’ I’d better show you some of the items I drew.

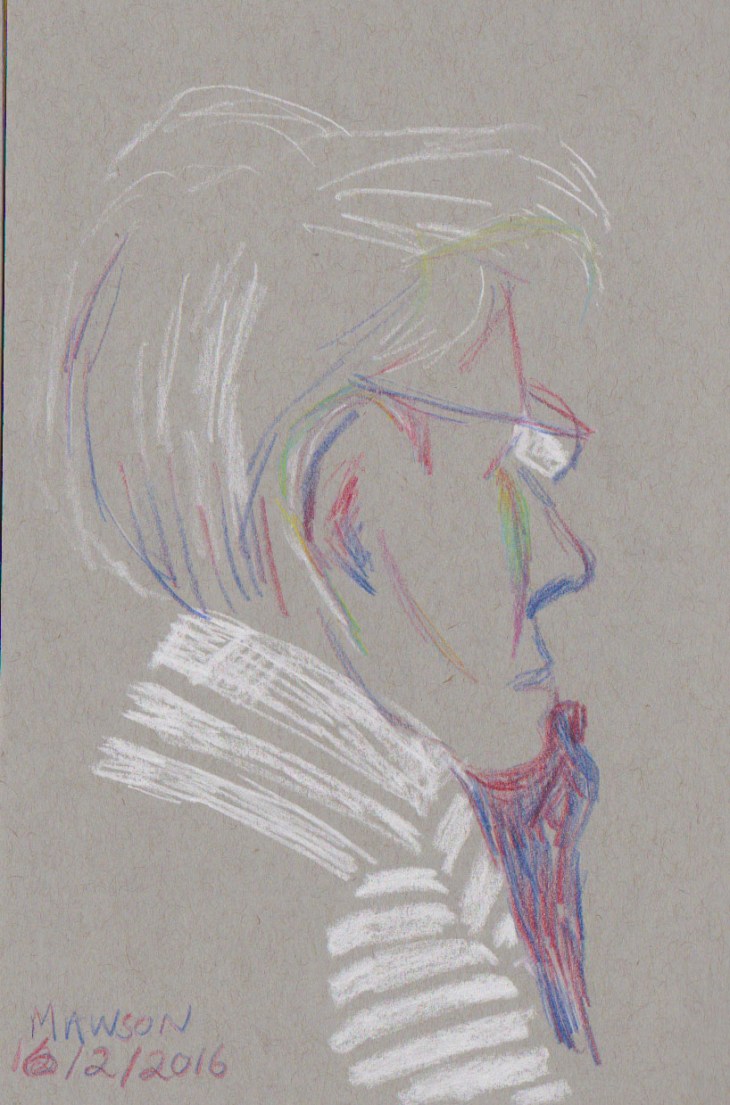

First up is a stone kodj, or axe from King George Sound, Albany in Western Australia, collected by Alexander Collie sometime between 1831-33. This kodj was one of the tools used for butchering animals.

Kodj, (axe), stone, resin and wood British Museum Oc. 4768

Two large stone flakes have been hafted onto a wooden handle with resin (not sure what type, but possibly from a grass tree). The sharpened end was also used in the butchering process. The strange yellowish shapes I noticed on the handle turned out to be collection labels.

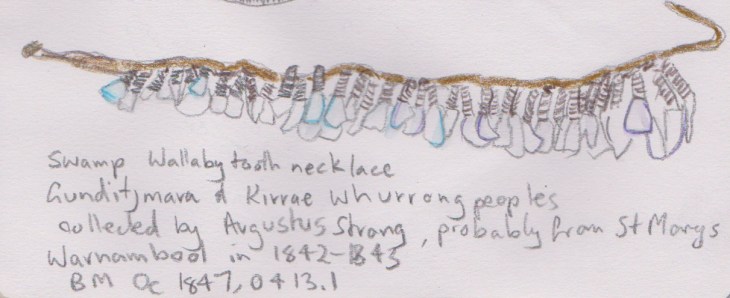

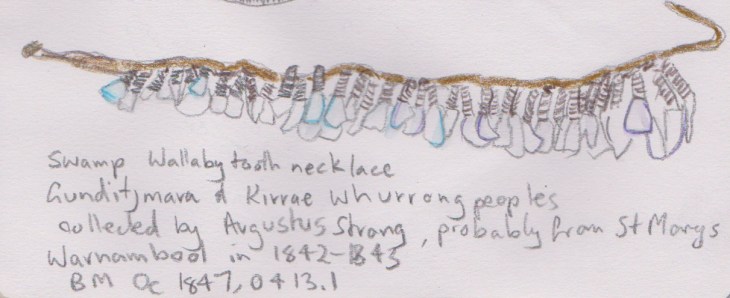

A more complex construction was that of a necklace made of swamp wallaby teeth, which was collected some ten years later on the eastern side of the continent. The root of each tooth was bound by fine string to a leather strap. The teeth are in excellent condition and appear quite white, with almost a blue or violet tint, hence the water colours I added when I got home.

Necklace of Swamp Wallaby teeth, Gunditjmara and Kirrae Whurrong peoples. Collected by Augustus Strong, probably from St Mary’s, Warnambool in 1842-43. British Museum Oc. 1847, 0413.1

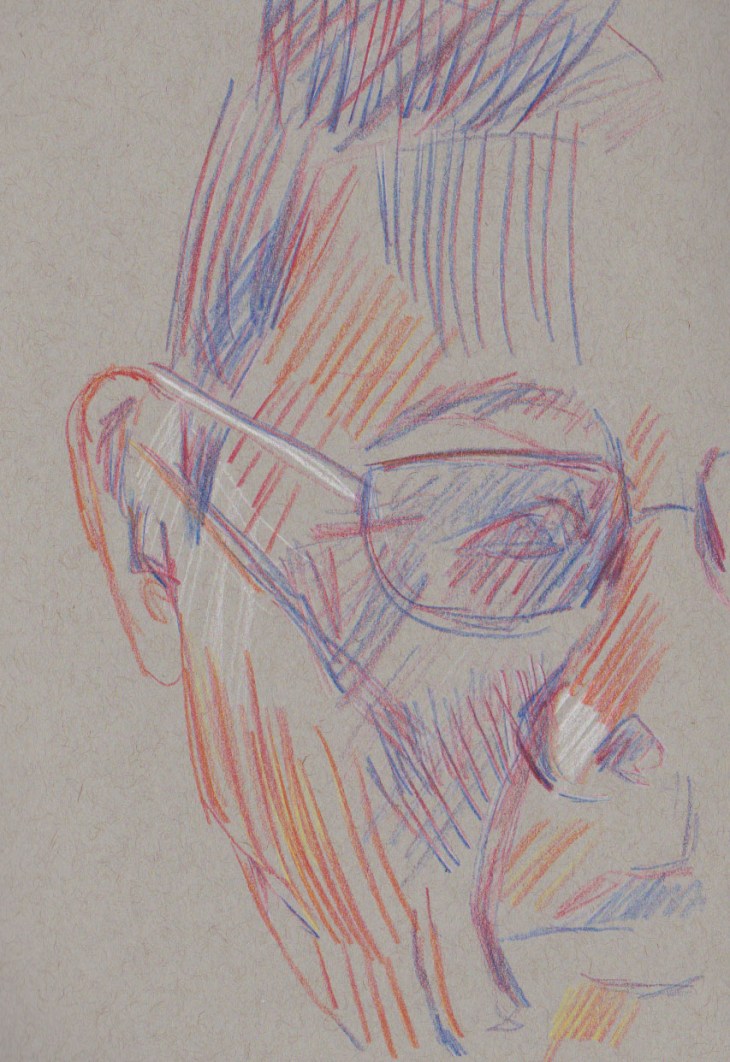

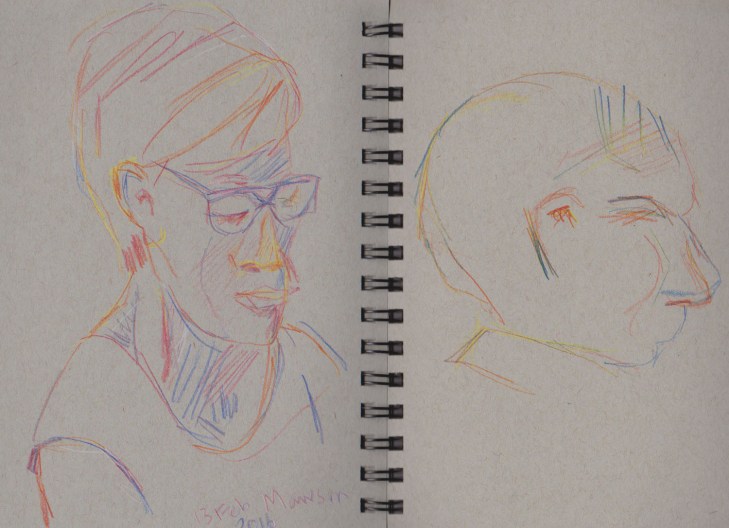

I also made two drawings of a Dangal, or dugong charm used for bringing good luck while on the hunt (well not to the dugong anyway).

Dangal (dugong) charm, collected by Alfred Court Haddon on Tudo in 1888

When I looked closely at this charm I could see what appears to be red ochre on it’s muzzle and also in a stripe along its back. The handle made of twine goes around the head and tail and a fine piece of twine is also threaded through the body of the animal via a small drilled out tube. This is such a refined a piece of work.

Per usual there’s so much more I wanted to draw, but there was more in store. Out the exit and into the next room is a second exhibition called Unsettled. This room showcases five contemporary Aboriginal artist’s response to the Encounters exhibition. I thought that this was one of the best small group shows I’ve seen in quite some time.

The work of Jonathan Jones is featured in a window that opens out into the main foyer. His work, Unitled (fort), reflects on a wooden fort built by surveyor and explorer Major Thomas Mitchell and his party of 21 men on 27 May 1835 . The stockade was built to protect against possible attacks by the local Kurnu Paakantji people. Fort Bourke was never attacked and no longer exists but Jones believes it remains a marker of still unresolved frontier relationships.

Untitled (fort), Jonathan Jones , 2015, wood

I was also really impressed by the video work of Torres Strait Islander dancer/artist Elma Kris and the contemporary take on traditional burial poles by Yolŋu artist Wukun Wanambi.

I would highly recommend both exhibitions. On at the National Museum of Australia, until 28 March 2016. Entry to both exhibitions is free.