A major retrospective of Arthur Boyd’s work is currently on show at the National Gallery of Australia. Drawing largely on the donations of work that the artist made to the gallery in 1975, the show includes works in a range of media, from pen and ink, oil, oil and tempera, pastel and tapestry.

With a show of such magnitude I can only touch on a few points I found of interest. Firstly I agree with the friend who commented on the wide range of styles that Boyd employed or reflected over the years. To my mind Boyd’s early works went from reflections of the Heidelberg School (Australian Impressionism), then to a strong influence of the artist Albert Tucker. At the same time his drawings in pen, ink and wash have a decided renaissance feel to them, possibly enhanced by their mythological and biblical themes. By the time he gets to England you can see strong influences of Turner, particularly in his landscapes.

I also felt that the hanging series of work, such as the Nebuchadnezzar paintings and the ‘caged painter’ series, reset my response to many of the individual paintings I had previously seen. The Nebuchadnezzar series, depicts episodes in the wanderings of Nebuchadnezzar and includes quite lyrical works which I was unfamiliar with.

Arthur Boyd, Nebuchadnezzar’s dream of the tree 1969 oil on canvas 174.5 h x 183.0 w cm, National Gallery of Australia, 1975.3.95

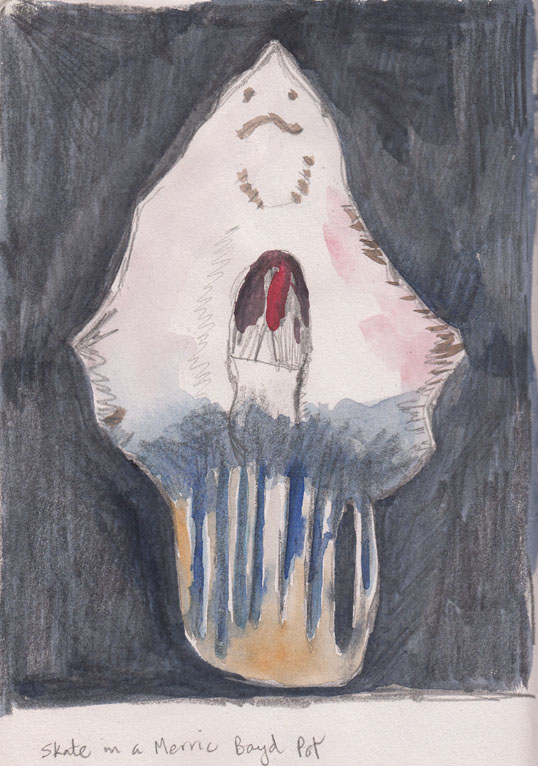

My favourite work was an oil, painted in 1979-80, titled A Skate in a Merric Boyd Pot. In this work a skate, an image which Boyd has painted many times, is merged with and is emerging from the type of pot that characterised the work of his father, the studio potter, Merric Boyd.

I spent a lot of time looking at the many examples of drawing displayed throughout the exhibition. Boyd showed the same facility with drafting, as did the young Picasso, then proceeded to refine and simplify his style as he grew more experienced.

Arthur Boyd, Figure in a fountain with watching figures 1944-1949 ink; paper , drawing in pen, brush and black ink 38.0 h x 56.0 w cm, national Gallery of Australia, 1975.3.1381

In his later works, the figures emphasise hands and feet, and faces are represented by blots for eyes and nostrils and small lines for mouths. These are no less powerful works for their brief notations. I tried to capture this focus in the quick study of the hands in one of the works in the St Francis tapestry series.

This final room is a fitting conclusion to the exhibition, showing nine of the 17 St Francis tapestries, designed by Boyd and superbly woven in Portugal at the Tapapecarias de Portalegre. As you approach, the works appear, glowing, quite literally with the strong colours Boyd used in his pastels, translated into the very large woollen tapestries.

For locals there are still another few weeks to see the exhibition, which runs until 9 November. Don’t be put off by the introduction of paid parking at the National Gallery. Visitors can validate their parking ticket at the cloak desk and will get free parking for 3 hours.