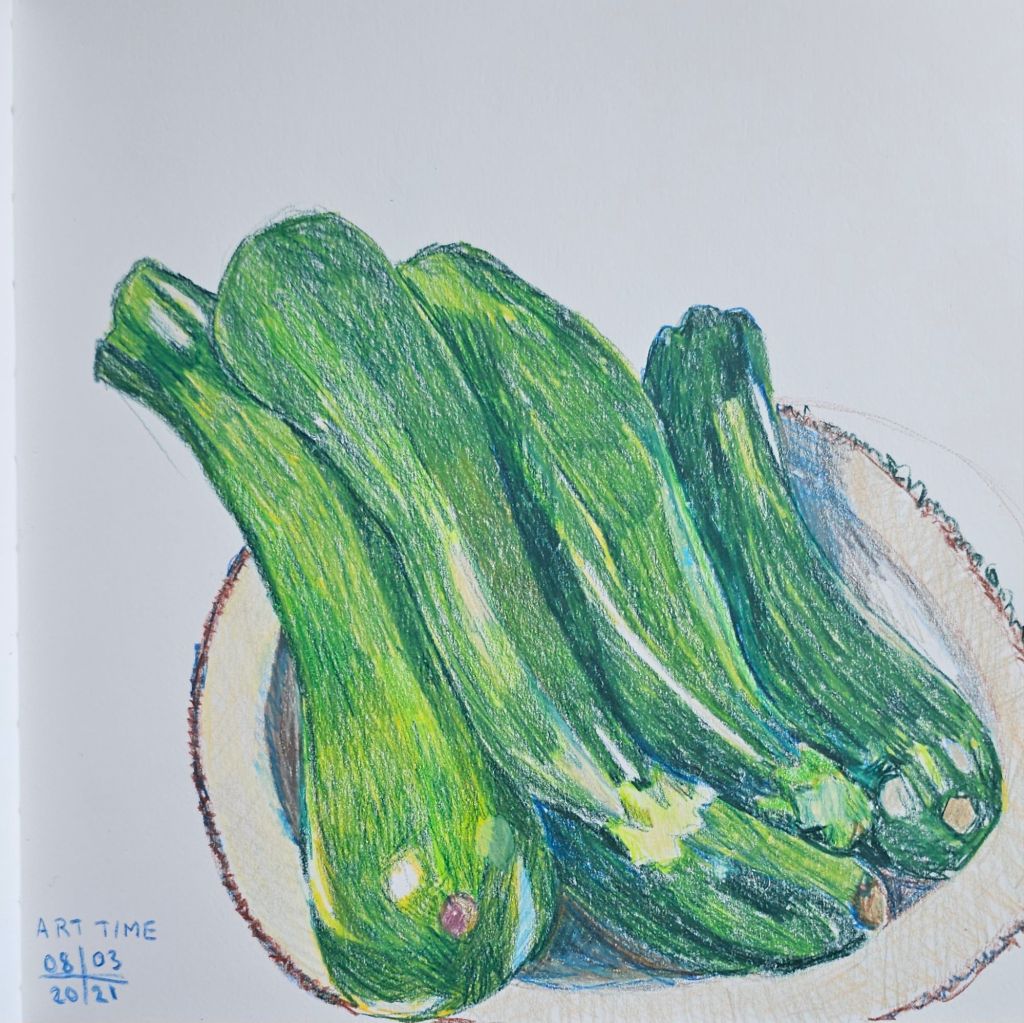

It started last year and now I’ve done two more sketches of the vegetables we grow in our garden.

The ‘Turk’s Turban pumpkin was a ‘no brainer’, so visually appealing it just begged to be drawn. Sadly, by the time we decided to eat it, it had rotted on the inside. I did manage to save some seeds so hopefully I’ll have more subjects next year.

Next up was this ‘Grosse Lisse’ tomato, which weighed in at 554 grams (or 1 pound 2 ounces). It was picked still a bit green, but has subsequently ripened fully.

Last but not least are a small bunch of zucchinis (courgettes), some of the 150+ fruits that we have harvested so far this year.

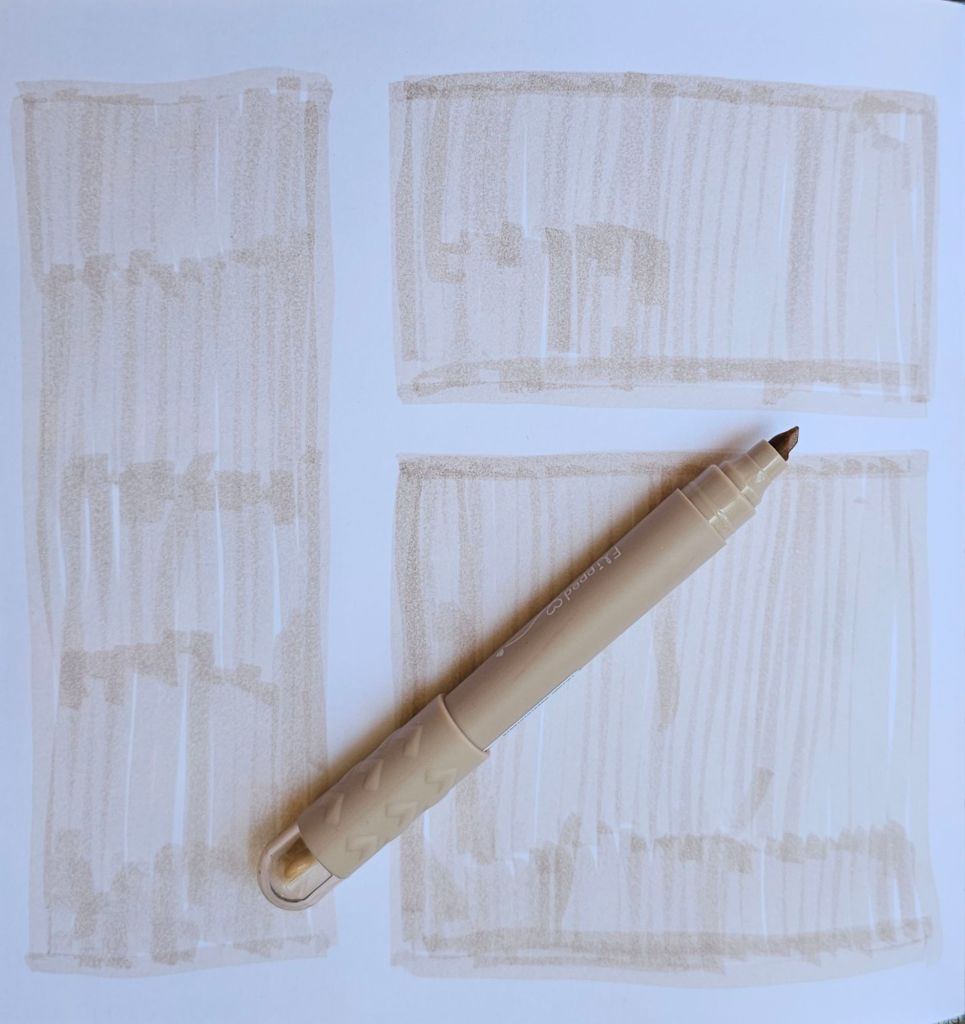

All the sketches are made using Caran d’Ache Luminance, light fast, colour pencils. My sketchbook is a Leuchtturm 1917 sketchbook, the combination of the smooth paper with the creamy pencils works particularly well.