During my brief stay in Adelaide I visited the Art Gallery of South Australia to see a ‘mini’ exhibition of calligraphic works on display in their Asian galleries. The exhibition, Brush and Ink, Contemporary Asian Calligraphy, displays large scale calligraphic works from China, Japan and Mongolia.

Japanese artist and commercial designer, Hiroko Watanabe’s installation takes up the end wall of the room. According to the room notes the 3D nature of this work is reflective of her work making commercial light-boxes to be placed on buildings. I always like to see ‘gesture’ in drawing and this work has it in bucket loads. I gather from the various reviews of this work that it was actually made during a performance with the group Above the Clouds, as part of the OzAsia festival. An interesting review of Watanabe’s performance can be found here.

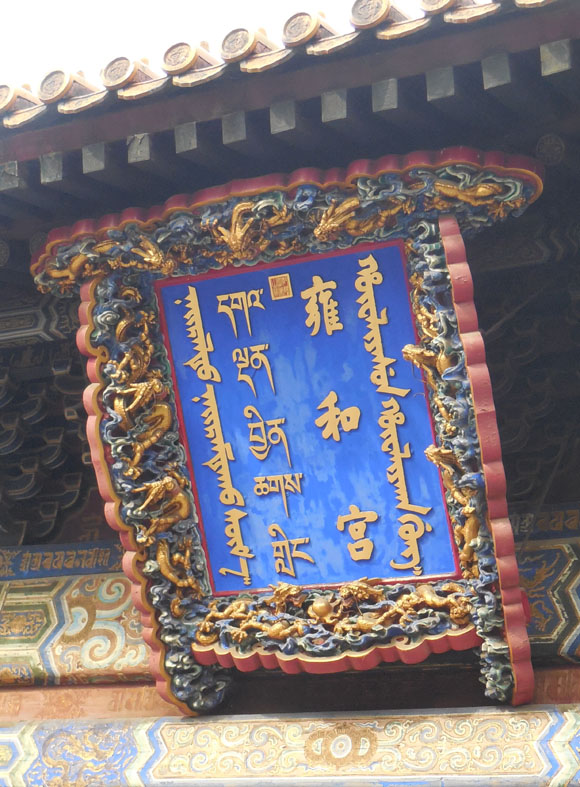

The Mongolian calligrapher’s were a revelation, quite literally I have never seen any of this calligraphy before and I only recently learned that there was a Mongolian script. This plaque attached to the Yonghe (Lama) Temple in Beijing is written in 4 distinct scripts from left to right as you see it Mongolian, Tibetan, Chinese and Manchu.

Inscription on the Yonghe Temple Beijing in four scripts, (l to r) Mongolian, Tibetan, Chinese and Manchu.

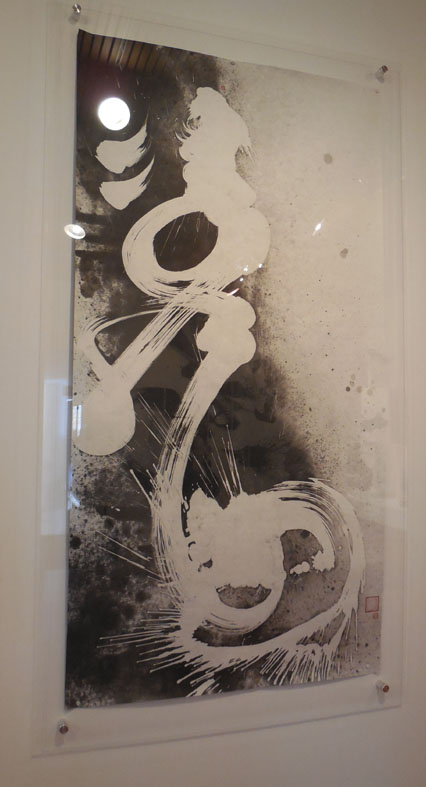

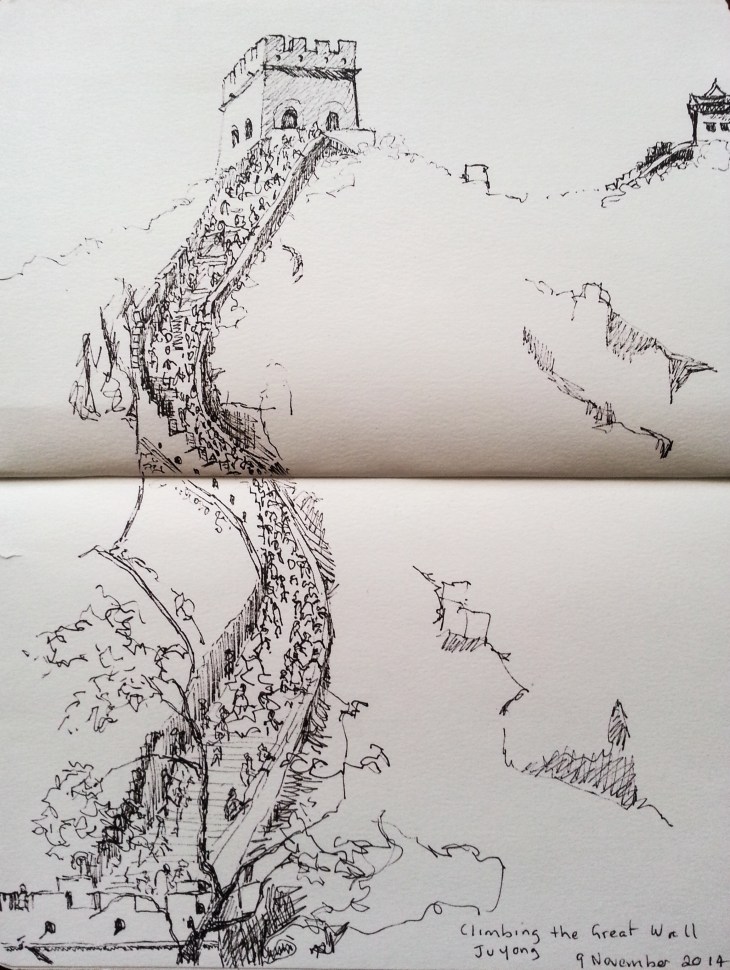

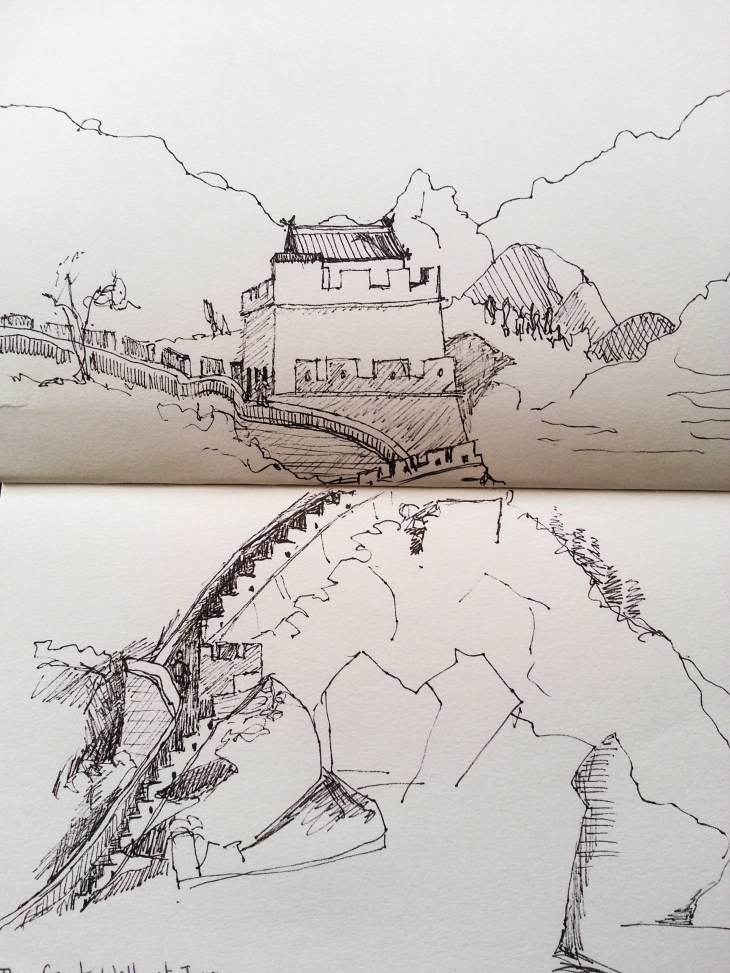

The exhibition room notes say that ” calligraphers from Mongolia often describe the physical act of writing from the top down in one fluid motion, ‘as a man riding a very fast horse’, or like a falling coin'”. I can only concur as the overwhelming sense I had of these works was of their dynamic motion. This ceiling to floor work by D Ganbaatar is a case in point.

I’m still trying to understand how this work “Aspiration”, by Lkhagva Tuvshinjargal, has been made (apologies for the light reflections in the photo, they were unavoidable). I couldn’t tell if this was white ink on a previously prepared paper or some type of reductive technique, like bleach taking colour out of a dark cloth. If anyone knows how this technique is achieved I’d be interested to find out.

If you would like to see more of Lkhagva Tuvshinjargal work I found some on this Hungarian blog (Google translate works well as my Hungarian is non-existent).

I also enjoyed this small collection of calligraphy on ceramics, from the AGSA’s own collection, also on display as part of the exhibition.

Additional images of Mongol calligraphy can be found on the following sites:

Mongolian National Modern Art Gallery – calligraphy

Mongolian Calligraphy on Facebook