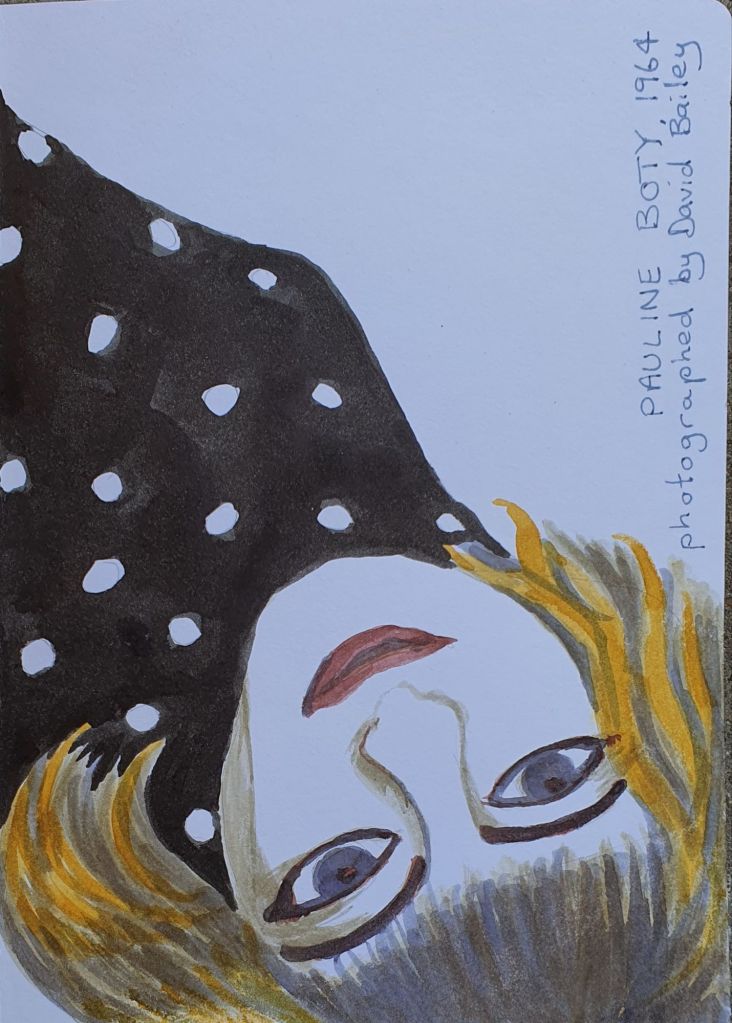

Pauline Boty, (1938-1966), was an English artist and sole female member of the British pop art movement. Boty came to prominance through unlikely paths. Initially she studied stained glass and then collage at the Royal College of Art. She had wanted to join the painting department but was dissuaded from applying because of the low success rate of applications by female students.

Drawn from a still from the film Pop Goes the Easel by Ken Russell, 1962

Boty’s good looks attracted attention, earning her the nickname of ‘the Wimbledon Bardot’ referring to her likeness to the French film star. Her appearance in the Ken Russell documentary Pop Goes the Easel, in 1962, gave rise to a series of roles on the TV and stage and one in the film Alfie.

In 1959 three of Boty’s works were selected for the Young Contemporaries exhibition and in 1960 one of her stained glass works was selected for an Arts Council exhibition Modern Stained Glass. You can see her stained glass self portrait in the National Portrait Gallery London.

Throughout her studies and in addition to her acting, Boty continued working on her paintings, first showing her work in a small group show in 1961. My favourite painting of hers is The Only Blonde in the World, 1963, a portrait of Marilyn Monroe, is in collection the Tate Gallery.

Boty married Clive Goodwin in 1963. In 1965 she became pregnant, but during an examination it was discovered that she had an aggressive cancer. Boty decided to forgo treatment as there could be no guarantee that her unborn child would survive. Her daughter, called Boty, was born in February 1966. Pauline Boty died of cancer in July of the same year.