It’s getting close to the end of the latest Winter Masterpieces show at the National Gallery of Victoria, Masterpieces from the Hermitage, so four of us decided to hop on a plane and head to Melbourne to spend a day with some of Catherine the Great’s collection, now housed at the Hermitage in St Petersburg. Catherine certainly collected a lot of art and other things in her time and lets face it, she had a lot of walls she could fill. So this exhibition is only a small sample of what she owned.

I’m always interested in what will catch my attention at this type of exhibition and here it was resoundingly the Flemish works and particularly those of Sir Anthony van Dyck. Per usual I chose to draw a number of works in the exhibition. In a situation when you are exposed to so many works of high quality it gives you some space to just sit and ‘be’ with a work, at least somewhat longer than the nominal art gallery average of 10 seconds per painting.

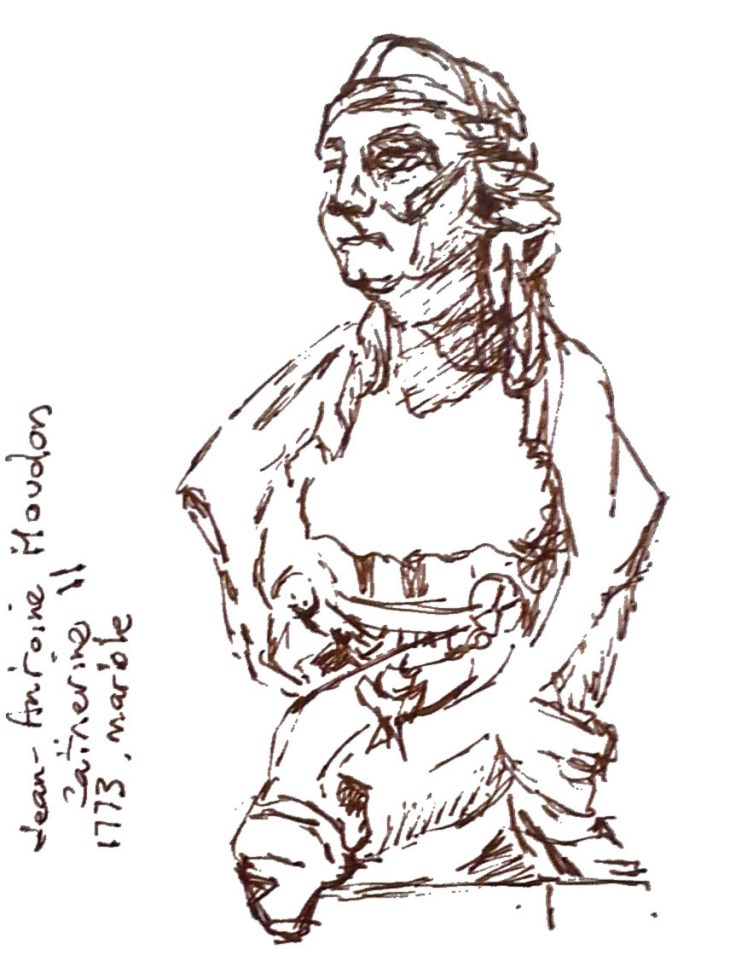

However in my hurry to refill my pens prior to leaving for Melbourne, I accidentally filled them with ink that does not really work with my Lamy, so apologies in advance for some scratchy pen work.

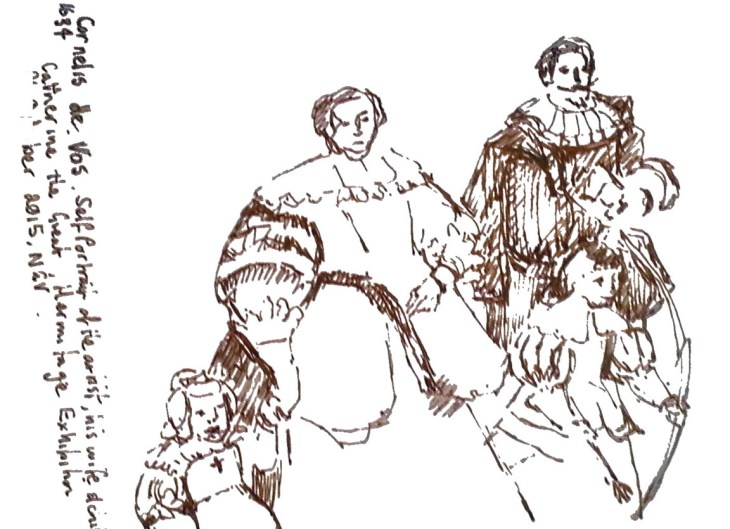

The first work to catch my attention was a family grouping by Cornelis de Vos, Self-portrait of the artist with his wife Suzanne Cock and their children.

Self-portrait of the artist with his wife Suzanne Cock and their children, c1634, oil on canvas, my sketch in pen and ink

My study doesn’t capture the older children of the family, just the two youngest, one holding a bow and arrow and the youngest on leading reins. In the original the parent’s clothes form large dark masses against which their faces and those of their children are naturally highlighted. From the quality and amount of lace, fine silk and jewellery being worn by the family you get the distinct impression that the art business was good for de Vos. I found his depiction of his young children particularly charming.

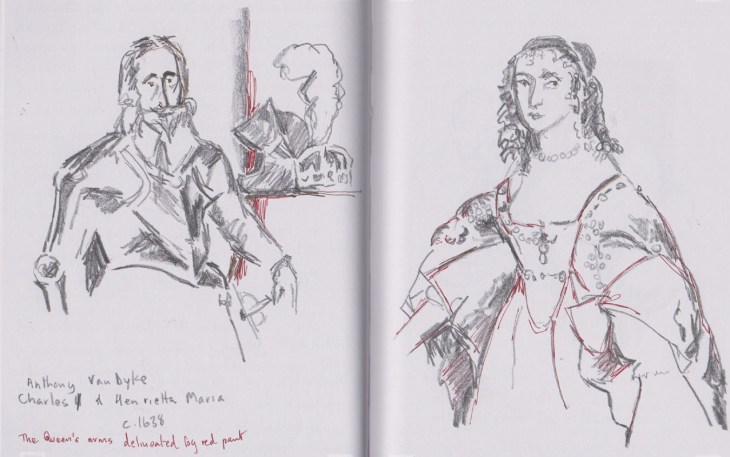

A large leap up the social ladder from the wealthy merchants that de Vos painted are Sir Anthony van Dyck’s paired portraits of Charles I of England and his Queen Henrietta-Maria. At over 2 metres in height they dominated the room they were hung in. The refinement of their faces, the lustre of the armour, silk and pearls made them hard to look away from, as was no doubt intended.

The flattery of van Dyck’s paintings was such that when Sophia, later Electoress of Hanover, first met Queen Henrietta Maria, in exile in Holland in 1641, she wrote: “Van Dyck’s handsome portraits had given me so fine an idea of the beauty of all English ladies, that I was surprised to find that the Queen, who looked so fine in painting, was a small woman raised up on her chair, with long skinny arms and teeth like defence works projecting from her mouth…”

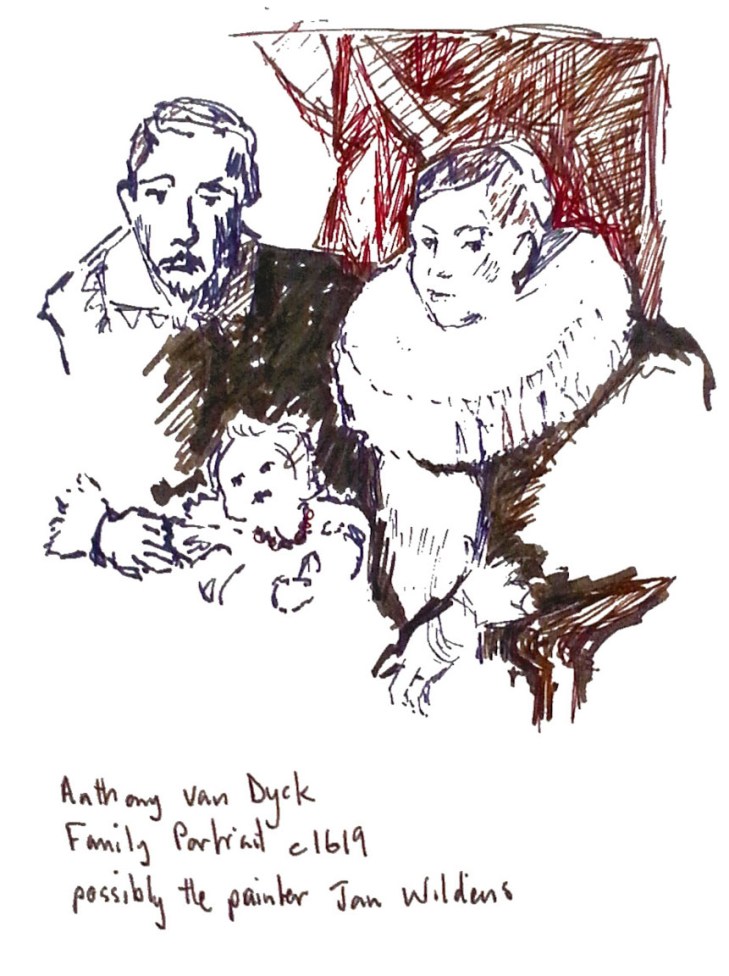

Perhaps truer to life was a smaller portrait that van Dyck made in 1619, the year after he was admitted to the Guild of St Luke as a free master painter. The Family Portrait, is thought to be of another artist, possibly Jan Wildens (in an interesting link, Wilden’s half sister, Suzanne Cock was the wife of Cornelis de Vos). His attractive young wife sits next to him while their young child, sits in his/her father’s lap looking upwards.

As you can see from the above study by this time I was resorting to every pen I could find in my bag just to complete the study. I’d spent most of the day in the exhibition, with a break for lunch and I was pretty exhausted. I staggered out of the gallery to have a restorative cup of coffee and lemon curd tart. Since checking up on the details for this post I have realised that there were any number of works I would have liked to go back and study in greater detail and some I managed to miss altogether.

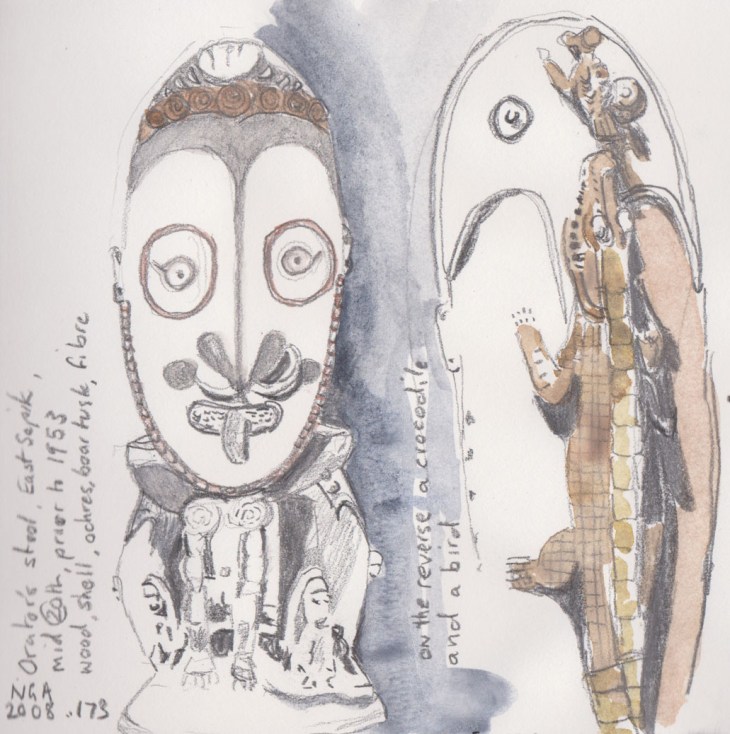

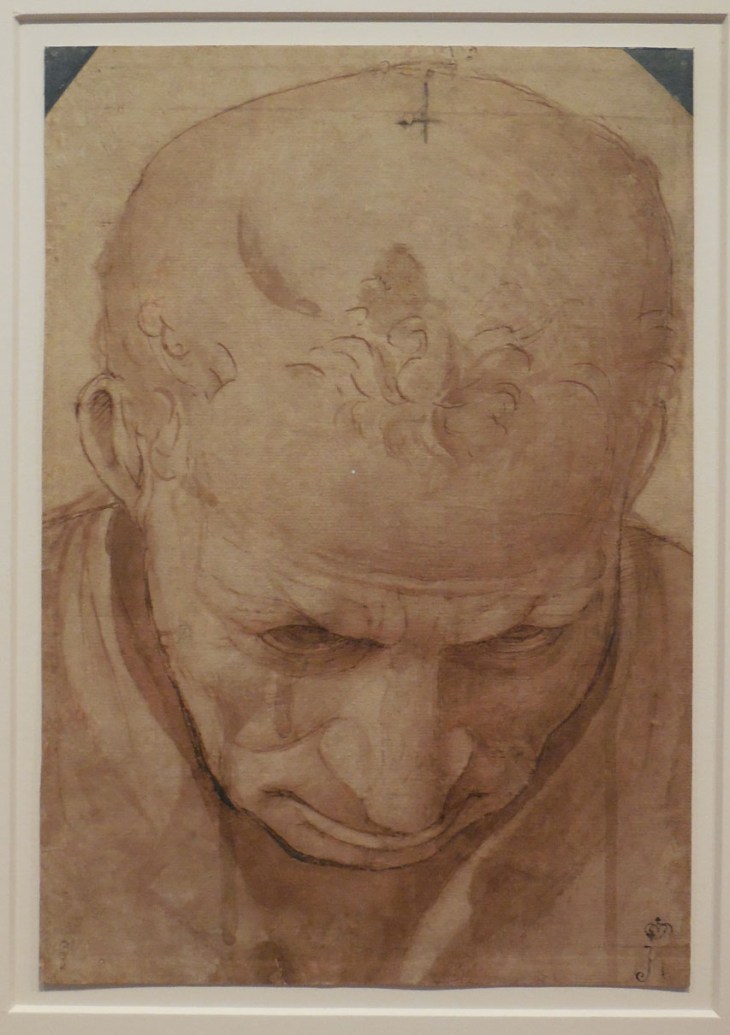

Here are two of the many amazing sketches that also caught my eye on the day.

Luca Signorelli, c1480, study of the head of an elderly man, pen and brown ink and wash, State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg