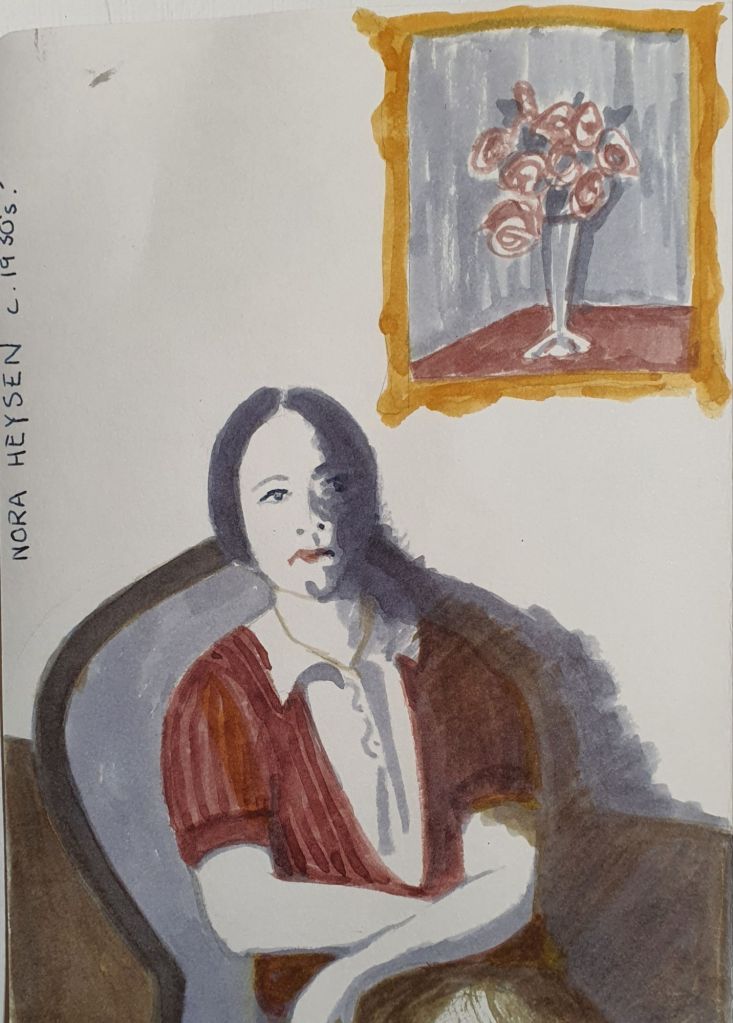

Nora Heysen (1911-2003), was the first Australian woman to win the prestigious Archibald Prize for portraiture in 1938, for her portrait of Mme Elink Schuurman. At age 27 she was and remains, the youngest ever winner of the Archibald Prize. The Australian Women’s Weekly subsequently summarised this landmark achievement with an article entitled “Girl Painter Who Won Art Prize is also Good Cook”.

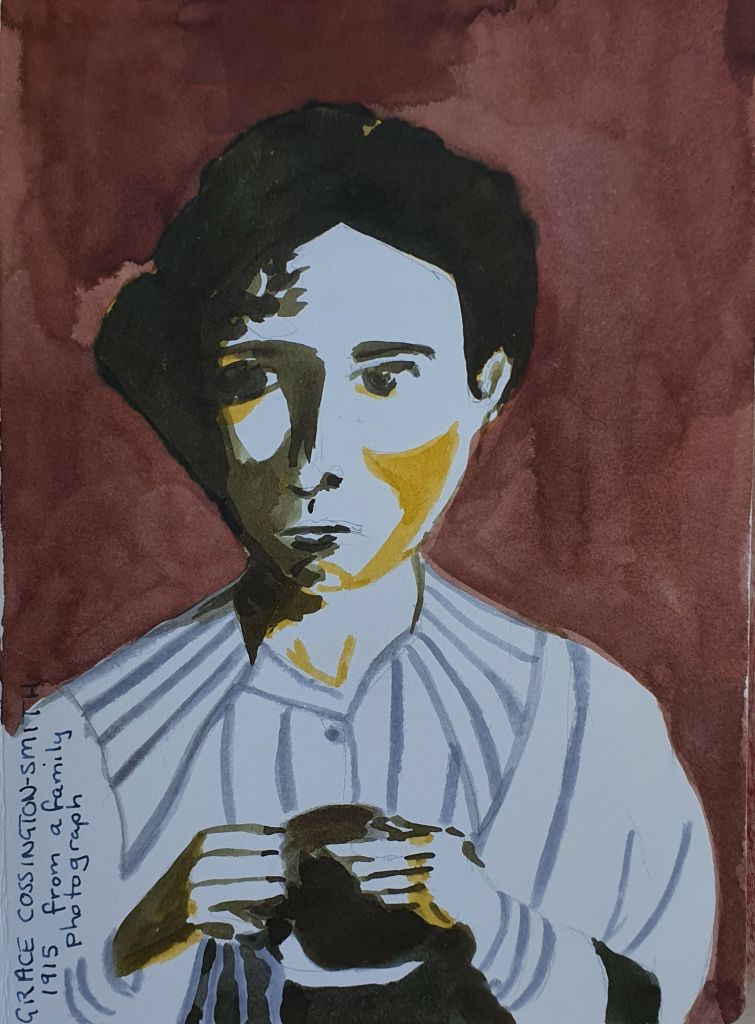

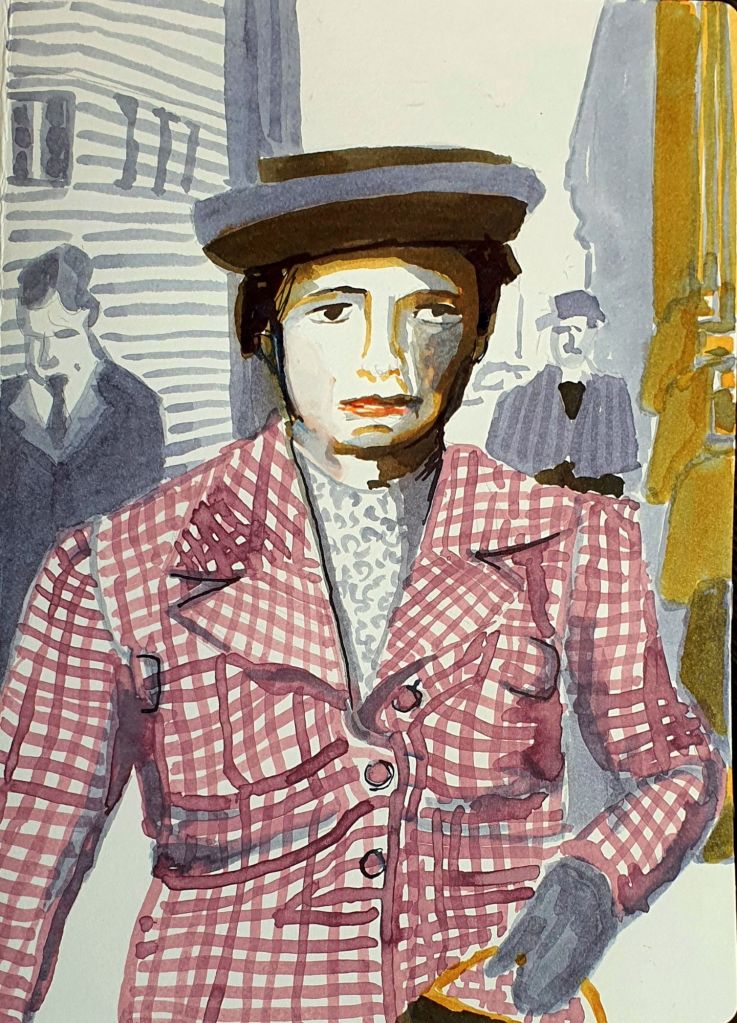

Despite underwhelming assessments like that, Heysen was more than capable of holding her own when it came to making art. The daughter of one of Australia’s most popular landscape artists, Hans Heysen, she began her formal art training at the age of 15 and by the age of 20 had her work in the collection of three State galleries.

Sales from her first solo exhibition in 1933 funded further study in London (1934-37).

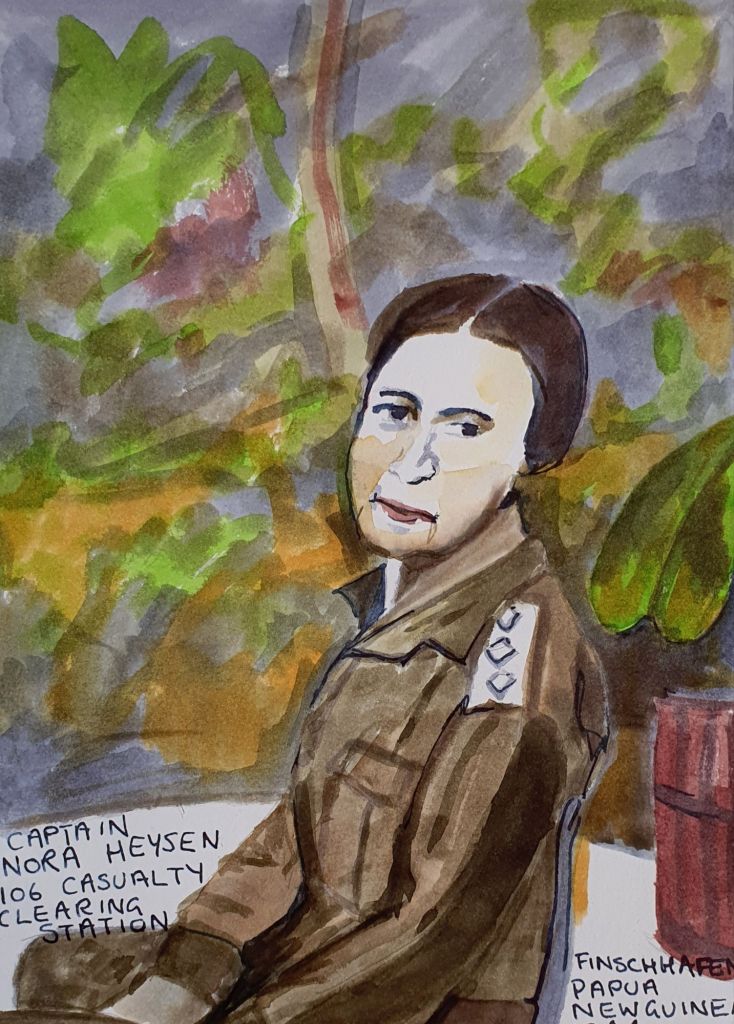

In 1944 Heysen made another breakthrough when she became the first Australian woman appointed as an Official War Artist*. In addition to her honorary rank as Captain, she was, with persistence and backing, even paid the same rate as male war artists!

One of my favourite portraits of her war service is of WAAAF cook, Corporal Joan Whipp.

Heysen married in 1953, but found her practice was disrupted. She and her husband divorced in 1976. By then her portraits and still life subjects had fallen out of fashion and her work was not recognised.

Later, while researching work on some of her father’s paintings, curator Lou Klepac saw her work, and recognised it’s quality. He mounted a major exhibition of Nora’s work in 1989. In conjunction with the National Library of Australia, Klepac held another successful exhibition of her work in 2000.

Unlike so many other female artists Heysen did live to see her work regain it’s prominence. She died after a short illness in 2003.

*Both Iso Rae and Jessie Traill documented the First World War in France, but neither were given official status as Government appointed war artists.